|

The Greek Age of Bronze

Chariots |

|

The chariot, probably invented in the Near East, became one of the most innovative weaponry in Bronze Age warfare. It seems that the Achaeans adopt the chariot for use in warfare in the late 16th century BC as attested in some gravestones as well as seal and ring. The use of the chariot was more likely diffused in the Greek mainland from the Near East after the Middle Bronze Age (about 1950-1550 BC) as a result of the Central and East Europe migration flows and Achaeans' trade contacts with that regions. It seems in fact that the chariot does not seem to have come to the mainland via Crete, but the other way around. It was not until the mid 15th century BC that the chariot appears on the Crete island, as attested by a seal engraving and the linear B tablets. The Achaean chariots can be conventionaly divided into five main design which can be identify as "box-chariot", "quadrant-chariot", "dual-chariot", "rail-chariot", and "four-wheeled chariot". The first two and the "four-wheeled chariot", in different variants, are attested since the early period of the Late Helladic time. The "dual-chariot" is attested since the middle of the 15th century BC and"rail-chariot" seems appeared only around the LH IIIB (about 1300 BC) when this horse-drawn weaponry was not only used as mobile fighting vehicle but also as battlefield transport. Both these utilizations are in fact also mentioned in the Iliad (*1). Despite the general opinion horse-mounted warriors were also used during the Late Helladic time even if the main utilization of the horse was as chariots drawer.

No complete Achaeans chariots survived even if some metallic parts and horse-bites have been found in some graves and settlements furthermore chariots bodies, wheels and horses are inventoried in several Linear B tablets. |

| On a gravestone from the royal Shaft-grave V in Mycenae dated LH II (about 1500 BC) there is one of the earliest depiction of the chariot in Achaean art. This sculpture shows a single man driving a two-wheeled small box chariot. The man on the chariot holds in his left hand a sword which is still in the sheath. In his right he holds a long object, which ends at the horse's mouth, and which being at first thick and becoming gradually thinner, resembles much more a lance than the reins; and it is difficult to say which of the two the artist intended to represent.A man on foot stands placidly in front of him holding a large club, stick or sword. This representation it has usually been understood as an Achaian warrior running down his opponent, nevetheless it has been also argue that the scene could instead represent an aristocrats at funeral game, where chariot races were later the highest entertainment for trained men at death of King. |

|

|

In another gravestone from Mycenae dated from the same period another small box-chariot is represented, in this case the reins hold by the singol charioteer are well indicated by one broad band. The chariot-box is here exceedingly low, and very small when compared with that of the chariot on the other tombstone, but it is not less remarkable, because it is surrounded by a band or fillet. The adversary on foot assaults the man on the chariot with a long lance , on which can be seen an object of a peculiar form, which much resembles one of the plain Trojan idols (*2), and must have served to attach the lance to the shoulder. |

| A stele with a possible hunting scene is also from the royal-shaft grave circle in Myceane. Also in this case a single man is driving a two-wheeled small box chariot. A dagger or short sword is probably hang on the man right side at waist level.

As for the other similar chariots also in this one the four-spoked wheels are positioned near the centre of the cab, and a shaft running horizontally from the yoke to the front of the cab further strengthened the vehicle. |

|

|

In this gold signet ring from shaft grave IV in Mycenae dated LH II (about 1500 BC) a bow-armed warrior and his chariot-driver are represented hunting from a small box-chariot. This representation shows that the chariot was also used by the Achaeans as archery platform even if its main utilization in the Aegean areas was normally associated with Javelin or spear(*2a). |

| A Box chariot with single occupant is represented in this cylinder seal of amethyst from Kazarma found in a tholos tomb dated LH IIA. |

|

| These early Achaean small box-chariots began to differ in terms of design from the Near Eastern type. The four-spoke wheels seems to be a standard throughout this period but it was made stronger and more robust. The axe was positioned near the centre of the cab and a draught pole was also located horizontally attached to the upper central part of the cab. The cab itself was framed in steam-bent wood probably covered with ox-hide or wickerwork, the floor consisting more likely of interwoven rawhide thongs. These early small box-chariot was crewed either by one single man or two men, a charioteer and a warrior. Armament for the chariot single warrior consisted of a throwing javelin or spear, while in the two men chariot, the bow was also used. |

|

|

A possible box-chariot seems also represented in this seal from Padiasos Crete dated around 1460 BC. This is one of the early representaton of chariot found in Crete. More likely the utilization of chariots has been introduced in Crete around in this time by the Achaeans coming from the Greek mainland. | .

| A beautiful box-chariot covered with wickerwork is shown in this seal from Thisbe Boeotia dated LH II (about 1500 BC). Even if the autenticity of the seal-stones from the Thisbe "treasure of seals" is actually questionable their iconographic model are significative being more likely based on real speciments. | .

|

|

A biger Achaean box-chariot of the early period is engraved on this carnelian seal from Vapheio dated to the 15th century BC. In this very interesting seal both the spearman and the driver are shown as well as the sturdy double upper-and-lower draught pole with lashed braces. Also in this case the cab structure seems coverd with wickerwork. |

| Similar box chariot but with a single man is probably also represented in this gold ring dated 1500-1400 BC part of the Aidonia treasure. It is difficult to determinate if the long object on the right hand of the man represent a javelin or a long stick used to whip the horses. |

|

|

A large box-chariot with bow-armed warrior and driver seems represented on this Achaean-Cypriote seal from Cyprus dated XV-XIV century BC.

Even if in very schematic way the sturdy double upper-and-lower draught pole with lashed braces and the reins are identifiable. |

| A schematic box-chariot is more likely represented in this hunting scene on a small seal from Rhodes dated around XIV century BC. The hunting warrior is equipped with crested helmet and large composite bow. |

|

| In this other small seal from Enkomi Cyprus dated around XIV century BC a small box-chariot with bow-armed warrior is also represented. In this case the chariot seems equipped with six-spoke wheels similar to the ones of the near easten (Egyptian and Hittite) type. |

|

|

A box-chariot with two men seems represented on this bronze plaque from the "Kadmeion" palace in Thebes dated about XV-XIV century BC. A decorative motif on the chariot's box structure is also partially visible. |

| An hunting scene with a possiible box chariot is represented in a lapis lazuli hoard cylinder seal always from the "Kadmeion" palace in Thebes The seal carving is

poorly preserved, but traces of a charioteer holding reins and a whip, along with a rearing horse and falling hooved prey survive. |

|

|

A rare type of chariot, known only from few representation, is termed the quadrant-chariot. It appears to have had a D-shaper floor, its siding consisted of what were probably heat-bend rails, the rounded profile approaching the quadrant of a circle. Also in this type of chariot the sides were probably covered with ox-hide or wickerwork.

One of the early representation of chariot in Crete is from this carmelian seal from Knossos dated around 1450 BC. It shows a man in a quadrant-chariot drawn by a pair of horses. The man holds a whip in one hand and reins in the other. The zigzag effect over the horses' backs (As also shown in the above seal from Vapheio) indicates the lashed braces between the upper and lower poles. |

| An interesting quadrant-chariot is represented in this sculpture from Thessaly dated XIII century BC. This chariot shows similarity both with Aegean and Near Eastern chariots having only the lower curved draught pole without the upper reinforcement shaft running horizontally (similar to the Near Easter chariots) but it seems to have the typical Aegean strong four-spoke wheels. |

|

| A possible quadrant-chariot is also the one represented in this clay-model also dated XIII century BC. Very interesting the decorated box and draft pole |

|

|

Another possible representation of a quadrant-chariot which shows a mix of features between the Aegean and Near Easter chariots is from this ivory gaming box from tomb 58 in Enkomi Cyprus dated around XII century BC. The hunting representation shows a bow-armed warrior and its driver on a small Anatolian style chariot with six-spoke wheels. Indeed the curved draught pole is reinforced with the central shaft like in mostly of the Aegean style chariots. |

| A Chariot probably of quadrant type with a single occupant is also represented on a lentoid seal from unknown provenance dated LH IIIA . |

|

|

Four-spoke wheels quadrant chariots is more likely also represented on this pithos fragment from Analiondas-Pareklisha Cyprus dated around 1300 BC. The representation consists of a hunting scene and both the chariot (except for the four-spoke wheels) and the hunter may recall Egyptian representations even if the rest is of Aegean inspiration. |

| A similar scene with another four-spoke wheels quadrant chariot with a quiver hanging from the side is probably also represented on this other pithos fragment from Analiondas-Pareklisha Cyprus dated around 1300 BC. |

|

|

Another interesting representation of a Four-spoke wheels quadrant chariots from Analiondas-Pareklisha Cyprus dated around 1300 BC. |

The dual-chariot was one of the most largely used chariot in the Aegean area. It is characterized by semi-circular extensions attached to the back of the chariot box. These extension were unknown outside the Greek-influenced areas. They were probably made from heat-bend wood with either textile or ox-hide stretched across the frame. The box also seems to have had the same covering, which enclosed it on three sides.

One of the early representations of this type of chariot is probably from this seal found in Pediasos Crete dated around 1460 BC. |

|

|

Very interesting representations of early dual chariots, each with single occupant, drawn by horses and griffins are represented on cylinder seal of haematite from Astrakous near Knossos Crete. These representation are dated 15th-14th century BC |

| A Dual chariot with two occupant, and drawn by goats, is represented on a signed ring of agate from Avdu near Lyttos Crete dated LM II-IIIA |

|

|

|

Another Cretan reprentations of this type of chariot is probably from the Minoan larnax of Haghia Triada Crete dated around 1450-1400 BC. The two Aegean style chariots have four-spoke wheels and the boxes are covered with ox-hide. |

| This reconstruction of an Achaean dual-chariot shows the typical Aegean traction system composed by the lower draft pole, the upper horizontal shaft and the reinforcement vertical pole stay. The pole stay , which was L-shaped, was connected to the draft pole near the front of the box. Between the pole stay and the draft pole there were either leather thongs or wooden lashed braces that created an arcaded effect. |

|

|

|

In these fragments of painting coming from Knossos (left image) and Tiryns (right image) the part of the yoke and harnessing and the junction of the upper shaft with the pole stay are respectively shown. |

|

Part of the yoke and harnessing in decorated blue color are also visible on fresco fragment from the West House of Mycenae dated LH IIIB1 |

| Part of the harnessing and the junctions are also represented in this chariot sculpure fragment from Mycenae dated LH III |

|

|

The harnessing and the junctions are also visible in this fragment from unknown provenance dated LH IIIA2 |

| Part of the yoke and the junction of the upper shaft with the pole stay are also visible in this fresco fragment from Mycenae dated LH IIIB2. |

|

|

Part of the chariot traction system is also visible in this fresco fragment from Tiryns dated LH IIIB2. |

This fresco from the palace of Tiryns dated LH IIIB (about 1300 BC) depicting a dual-chariot. The frame is covered in red hide or fabric cover. The utilization of red hides and crison are also attested from the Linear B tablets.

Several evidences of Achaean roads that are suitable for wheeled trafic have been reported for the Argolid, Messenia, Boeotia, Phocis and Crete. These carriageable roads were more likely used either to facilitate the military chariots movements from the palaces to the battlefield or to commercial and trade roads for civilian chariots traffic as well as for wagons trasporting agricultural goods. |

|

|

Two armed warriors and a dual-chariot are depicted in this fresco from Pylos dated LH IIIA/B (about 1350 BC). This example appears more lightly constructed than the other dual-chariot (perhaps it was used more for trasporting infantry than battle-vehicle) In this chariot the cab's lateral sides, covered with hide or fabric painted in yellow color, are made in a sigol piece unlike the other dual-chariot in which the semi-circular extensions are attached to the back of the chariot cab. The cab upper double lines could be intended as the frame of the box made with double rails as also attested in the Iliad (*3) |

| Similar chariots could have been also represented in the fresco of the "Megaron" from Mycenae dated between LH IIIA and LH IIIB (1370-1350 BC). The complete battle scene with warriors and charioteers, is only hypothetically reconstructed and fully questionable being the few survived parts of the fresco very fragmentary. |

|

|

|

Parts of chariot from a fresco fragments representing a boar hunt scene in the Palace of Orchomenos dated LH IIIB1. The chariot box shows an unusual pattern decoration with black crosses on the white background of the box pannels. |

| From the same fresco another fragment shows a chariot box with a zigzag pattern probably representing the wicker structure of the box pannels |

|

|

Even if the question how the Achaeans used chariots in warfare is still controversial, it seems that, based on the pictorial scenes, they did not use their war-chariots in the large squadron mass charges in the manner of the Near Eastern kingdoms and Egypt. There are very few and questionable images of chariots being actually used on the battlefield in the Aegean pictorial art, indeed based on some hunting scene and armed charioteers representations, Linear B tablets as well as Iliad descriptions there is no question that the chariots were largely used in warfare both as platform for throwing javelins, or when possible thrusting spears (*4), and for bow-armed warrior. In the later period the more lightly constructed dual-chariot and the rail-chariot were mainly used as a means of conveyance to and from battle, even if in some specific scenarios their utilization as fighting vehicle with spears, javelins and long swords can't be completely excluded. |

| Dual chariot with two occupant is probably represented in this sculpture from Markopoulou dated LH III |

|

|

Parts of chariot is still visible in this pottery fragment from Mycenae dated around LH IIIB. The white dots could decorative or embossed metal elements. |

| In this Achaean crater from Enkomy Cyprus dated around 1400 BC a dual-chariot is well represented. The dots motif on chariot-box and human's garments could represent both decorations, untanned animal skin or metal decoative elements. It seems also that similar ox-hide or decorated fabric. |

|

| Large dual-chariot with three men is represented in this crater from Aptera Crete dated around 1400 BC. Also in this case the cab's sides seem to be decorated with geometrical motif. The utilization of metal decorative elements on the Achaeans or enemy chariots is also attested in the Iliad (*5) |

|

| Several representations of dual-chariot are visible in the Achaean pottery coming from different mediterranean and Greek mainland areas. The first chariot on the upper row from left is depicted on a crater from Enkomi Cyprus dated around 1400 BC. the cab seems covered with scale reinforcements more likely metal decorations. The second in the upper row is also from Cyprus dated from the same period. It is interesting because it has six-spoke wheels and the cab seems covered with ox-hide. The third one in the upper row is another dual-chariot also from Enkomi Cyprus coming about from the same period.

Another large Achaean dual-chariot with three men, depicted on a pottery from Aradippo Syria, is shown in the first image from left in the lower row. The second image in the lower row represent a dual-chariot from Mycenae dated LH IIIB (about 1300 BC). Inside this chariot three men with a large parasol are represented. The last image in the lower row is very interesting because represent a dual-chariot depicted on an Achaean amphoroid krater fragment found in Tell el-Muqdam Egypt. This fragment has been found together other decorated faience fragments bearing cartouches of Ramesses II, Merneptah. |

|

| An interesting design element analysis of the structure of the chariot box has been made by Christine Morris in his article DESIGN ELEMENT ANALYSIS OF MYCENAEAN CHARIOT KRATERS: STYLE, COMPLEXITY AND SIGNIFICANCE (*5a). |

| A very interesting dual chariot pulled by griffin is depicted in this Achaean krater found in Tomb 43 from Enkomi Cyprus dated LHIIIB (about 1250 BC). The griffins, which has birds' head and lions' body is often seen accompanying a deity. |

|

|

Even if sometimes described as a rail-chariot this scene depicted on a krater from Tiryns dated LH IIIB2 (around 1250 BC), more likely shows a dual-chariot being its box dimension and general shape more similar to the ones of the dual-chariots type. This chariot is also comparable with the one represented in the above mentioned "Parasol krater" from Mycenae. |

| An Aegean style dual chariot with possible bow armed warriors is also represented in this pottery fragment from Ugarit dated LH IIB. The pottery has been found in the layer related to the destruction level 7A occurred between the 1220 BC and the 1180 BC and attribute to the Sea Peoples invasion. |

|

Only two Mycenaean chariot vases are known from Anatolia, and they are not directly associated with other chariot-related archaeological material. At Miletus, one fragment of a LHIII:A2–IIIB amphoroid chariot krater comes from the Athena Temple area in a lower level along a Mycenaean defense wall, and two bits were found in a chamber tomb of the Degirmentepe necropolis. This necropolis shows a strong Achaean influence, but the shape of the houses and the pottery used do not allow us to attribute any nationality to inhabitants.

Two fragments of Mycenaean chariot kraters come from Troy VI. Sherd VI.E.21 comes from the Earthquake area and the other one was found on the surface somewhere along the southern side of the Trojan Citadel (*12). According to stylistic criteria, they might derive from the same vase, but the reported places of discovery make it uncertain. |

|

|

|

In the Tholos Tom A of Kakovatos dated LH I / LH II a disc-shaped cheek piece of horse bridle made of ivory has been found. This ornamented has a diameter of 12.1cm. The front side of the cheek plate carries an orna-ment of bands with small cockleshells lin-ing the rim of the disc and forming a curved diamond-like shape around the four bosses in the centre of the disc. On the reverse of the cheek plate, four spikes can be securely reconstructed. Similar types occur in Shaft Grave IV of Circle A and Shaft Grave Γ of Circle B in Mycenae. Only a single example appears in a grave that would belong to a Cat-egory 3 context, in Pit 5 in Chamber Tomb 7 of Dendra.

|

| Cheekpieces part of horse bits have been found in several Achaean settlement sites, as these bronze specimens from Mycenae. |

|

|

Different kind of cheekpieces part of hourse bits have been found in the Achaean settlements. These specimens are dated around LH IIIB |

| Even if no complete Achaean chariots survived some horse-bites have been found in settlement sites, like these ones from Mycenae. Pheraps these bits were placed in the tomb in lieu of horse, as no horse bones were found in the same context. |

|

|

Two couple of well preserved bronze bits have been also excavated from an Achaean tomb at Miletus in the coast of Anatolia. |

This pair of bits dated around 1300 BC are one of three pairs of bits found in the "Arsenal" at Thebes. The pairing of these bits suggests that they were intended for a chariot team. Their find context in the "Arsenal" suggests that these chariots were part of the military equipment.

The rest of the bits from Bronze Age contexts have not been found in pairs; therefore they were more likely intended to be used on horse mounted. |

|

|

Similar pair of bronze horse bits have been also found in the Prosilio tomb 2 in Orchomenus dated around 1350 BC. |

| Late Achaean horse bits dated around 1200 BC from unknown location in Greece mainland (collezione Giannelli) |

|

|

|

Representation of cheekpieces are well depicted in these fragments representing part of heads of bitted horses respectvelly from Orchomenos and Tiryns both dated around LH IIIB2 |

| Another representation of bitted horse with cheekpieces is depicted on this fragment from Greek mainland (unknow provenance) probably also dated around LH IIIB |

|

|

These bronze bands and relevant nails found in Pylos dated around 1200 BC are more likely metal elements of a chariot. |

| Horse's bronze collar from Crete, unknow datation. This specimen is decorated with the typic Minoan double axes motif. |

|

|

Also this bronze element dated around XIII - XII Century BC from Crete is more likely a metal element of a chariot. |

| Bronze buckle from the gear of a horse, from Maa-Palaeokastro Cyprus dated aroud 1200 BC. Such objects have been found also at Enkomi and may have been part of the harnesses of horses. |

|

|

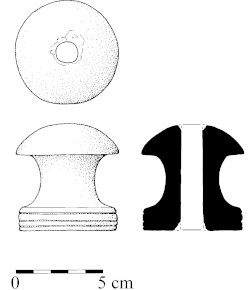

A bronze anthropomorphic chariot linchpin dated 11th Century BC has been found in the Philistine settlement of Ashkelon (Room 503). The pin represent a warrior with the typical "tiara feathered" helmet used by some of the Sea Peoples groups.

Similar object has been also found the the other Philistine settlement of Ekron |

In the same location a yoke-saddle knob has been also found. The proximity with the above mentioned linhpin suggests that they served as fittings for the same chariot.

The chariot parts found in the two leading city of the Philistine Pentapolis Ashkelon and Ekron indicate that the Philistine newcomers to the coast of Canaan were well equipped for chariot warfare agiants the Egyptians, Canaanites and the Israelites. |

|

|

|

|

The rail-chariot appears on Late Helladic vase painting generally dating to 1300-1150 BC. Because the very schematic representations the exact features of the rail chariot are difficult to reconstruct. Nevertheless, enough details can be pieced together from the various fragments to provide an idea of the rail-chariot's basic structure.

The rail-chariot was very light and characterized by an open frame, from which derives its name. The rail probably came up to the hip and ran horizontally over the front of the box. Variations in the representations suggest that the rail may have curved upward at the front corner.

The possible early representations of a rail chariot are attested on a seal from Aghia Triada Crete dated around 1400 BC, and larnax from Kavrochori Crete dated around LM IIIB. Another early representation of a rail-chariot is from a krater from Mycenae dated LH IIIB (about 1300 BC), even if the stylization of these early representation does not allow the identification of further details. |

| Rail-chariots are more likely also represented in this achaean krater from Pyla-kokkinokremos Cyprus dated LH IIIB. Even if this type of chariot is usually thought to be direct copy of an Egyptian design, several major differences lead to the conclusion that the Aegean rail-chariot was more likely not directly copied from the Egyptian, it may have been related to Egyptian chariots, as the box and quadrant chariots were, but ultimately the rail chariots has an indigenous development. | . |

|

|

Another representation of a rail-chariot is from this krater fragments from Tiryns dated LH IIIC (about 1200 BC). The late Helladic IIIB and IIIC depictions of rail-chariots, dual-chariot, and four-wheeled chariots were the last pictorial representations of wheeled vehicles until the mid-eighth century, when the chariot again became a popular subject for Geometric artists. |

| A rail-chariot is probably also represented in these krater fragments from Tiryns dated LH IIIB2 (about 1250 BC). The warrior on chariot is more likely wearing a chest embossed cuirass. |

|

|

These other krater fragments clearly reprenting a rail-chariot are also from Tiryns dated LH IIIB2 (about 1250 BC). |

| Two small rail-chariots probably pulled by a single horse and probably involved in a race or some kind of games are depicted in these krater fragments from Tiryns dated LH IIIC (about 1200 BC). |

|

|

A rail-chariot seems also represented in this krater fragment from Tiryns dated LH IIIC (about 1200 BC). |

| Two small rail-chariots probably also pulled by single horse are depicted on this krater found in a warrrior grave from Elis dated LH IIIC (about 1200 BC). |

|

| Though it is not entirely clear because the representations are somewhat sketchy, the frame of the rail-chariot probably also run along the sides of the cab. In some representations the two occupants seem placed one behind the other and not abreast, as is the usual convention in Achaean depictions and also attested in the Iliad (*6). The rail extends beyond the second occupant and behind the wheel. The screens that covered the cab of the dual-chariot were no longer utilized, and the "wings" were no longer added to the frame. Normaly the wheels of the rail chariot were four-spoke, even if the utilization of wheels with several spokes are also attested. The traction system is unclear as well, even if based on some representations both the system with a singol lower draft pole than the more robust Aegean style draft pole reinforced with pole stay and pole brace were probably used. The cab rail or wood frame of the chariots is often mentioned in the Iliad even if it is not clear if these chariots have to be intended as "dual-chariot" or "rail-chariot" type (*7). More likely both these type of chariots were used during the Trojan war. |

|

|

this pottery fragment from Tiryns dated LH IIIC shows as the Aegean traction system with draft pole reinforced with pole stay and pole brace was also used on rail-chariot. |

| Rail-chariots are also well represented in this fragmentary krater from Tiryns dated LH IIIC. Each chariot has a driver and shield-bearing spearman, these warriors seem equipped with corselet/armour, neck protections, crested helmet and greaves. |

|

|

In this pottery fragment from Tiryns also dated LH IIIC two warriors with "hedgehog" helmets small round shields, greaves and two javelings are depicted on a rail-chariot. |

Similar armed warriors riding a rail-chariot are also shown in this other pottery fragment from Tiryns always dated from LH IIIC.

After the end of the Bronze Age small rail-chariots continued to be used during the Geometric period in all the Aegean area. |

|

| Several small pottery fragments with possible representation of warriors on rail-chariots have been found in several Achaean settlement sites. The first from the left shows two warriors bearing round shields on rail-chariot. The fragment dated LH IIIC is from Mycenae. The second one from Tiryns dated LH IIIC shows a warrior with bell cuirass, belt and greaves on a rail-chariot. The third fragments always from Tiryns dated LH IIIC shows more likely a warrior equiped with armour on a rail-chariot. |

|

A rail-chariot seems also represented in this crater fragment from Morphou-Gnaftia Cyprus dated around 1200. This is a further evidence that the rail-chariot have been also used in the Achaean influence places outside the Greek mainland.

This type of rail-chariot is equipped with not common but sometimes used several-spoke wheels. |

| A similar rail-chariot is also represented in this crater fragment from Kynos dated LH IIIC. In this representation the artist carefully tried to paint every detail of the chariot, e.g., the yoke-saddle, the manes and the tails of the horses, the reins, the draught pole and the wheels. This chariot disply some peculiarities. Its wheels have ten spokes and a series of dots are painted along the outer face of the wheel. Obviously we are dealing with a metal sheathing of the wooden wheels. The dots represent the nails that fastened it. Similar exposed nails around the wheels are also visible in some chariot representations and models from the Near East. |

|

|

Very interesting Ryton partly in form of rail chariot from Karphi dated LM IIIC or Subminoan period. |

| A interesting model of a rail-chariot with similar design even if with four-spoke wheels has been found from the Sardinia Island Italy. This specimen is more likely dated around 900 BC. Several archaeological images and informations about the Bronze Age/Early Iron Age population of the Sardinia Island and their connection with the Sea Peoples can be found in this web site SHARDANA I POPOLI DEL MARE . |

|

|

A miniature model of chariot wheels with several spokes, very similar to the above mentioned fragment from Cyprus and Kynos, has been also found in Mycenae. |

| Eight-spoke wheel is also well represented in this pottery fragment from Tiryns dated about LH IIIC. This further representation shows that the Achaean do not utilized only the four-spoke wheel on their chariots. The utilization of eight-spoke wheels on war chariot is also attested in the Iliad (*8) |

|

|

A bichrome ware pictorial krater, dated 11th Century BC, depicting abbreviated chariot with six-spoked wheel and charoteer weared feathered helmet has been found in the Philistine settlement of Aschkelon.

Some scholars states that the "Greek chariot warfare virtually disappeared" after the Mycenaean IIIC period. Clearly, the Philistines of Achaean background had not yet received this message in the 11th Century BC. |

|

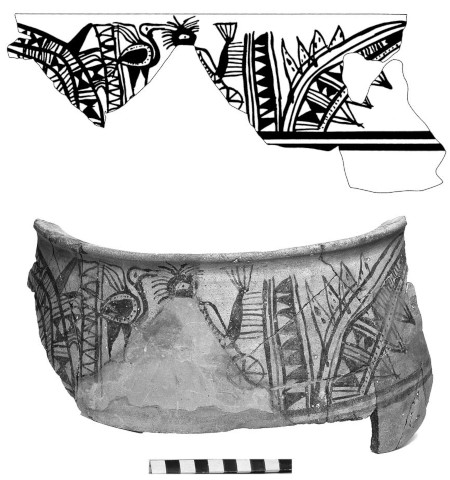

A strange type of chariot seems attested on a krater fragment from Khania Crete dated around LM IIIB2 (about 1250 BC). The pictorial scene painted on the preserved fragments shows two ears and part of a mane of a horse on the rim fragment and what is probably the hindquarter and long tail of the same horse on the body fragment. Behind the horse it is visible the lower part of a chariot with a carefully drawn four-spoked wheel and behind the chariot the torso, arms and upper legs of a tall warrior carring a sword at his waist. |

| The box of this chariot is rendered with an irregular network, which could indicate that it was made of wickerwork.The small dots at the base in front of the box may be part of a superimposed decoration. The box has a curved outline at the ear, and judging from the space left for it, it might have had the same height as the warrior (or even slightly higher). As a consequence to this, the box seems to have been covered. |

|

|

Contrary to the other known chariot boxes the one represented on this krater reaches the ground at the rear, an impratical solution for a chariot box if the space is not intended to be used. If it is depicting a canopied chariot, the person being transported is sitting down and the space could have been for the leg. Thus the box may actually have been open both at the rear and front. The scene may represent the moment when the coach and horse is standind still and the box reaches the ground. A confortable means of land transport for someone who needed an armed warrior for protection in insecure surroundings and insecure times? (*8a) |

|

Another chariot represented in the Late Helladic time is the four-wheeled chariot. Unfortunately, this chariot type is not well documented because the scenes in which it is depicted are quite fragmentary or very schematic. As a result also for this rare type of chariot its exact features are difficult to reconstruct.

A possible battle scene seems represented in this battered stele from Mycenae where is possible to identify a "battle wagon" four-wheeled in the Near Eastern fashion, with the warrior apparently plunging head first to the ground behind his charioteer. This stele dated around 1500 BC represent the earliest image of four-wheeled chariot utilized in the Greek mainland. |

| A very schematic four-wheeled chariot is represented in this seal from Cyprus dated around late XIII century BC. The scene is representing a bow-armed man hunting a deer from his chariot. |

|

|

Two four-spoke wheel more likely part of a four-wheeled chariot are also depicted in this potery fragment from Tiryns dated LH IIIC. |

| A strange four-wheeled vagon with three men is also represented on a larnax from Episkopi dated around 1300 BC. The solid painted circle on stem held by two of the figures in the chariot could represent parasols. |

|

|

Beautiful representation of four-wheeled vagon from Palaikastro Crete of uncertain datation. |

| In the Achaean to Proto-Geometric period cemetery of Voudeni some fragments from a large krater dated around 1200-1100 BC show a four-wheeled chariot. In these representation the four-wheeled chariots is utilized by a warriors equipped with low profile crested helmet and medium size round shield. |

|

|

Four-wheeled chariot is well represented in this crater fragment from Crete dated around 1100 BC. In this reprentation the lower draft pole is also visible as well as the frontal element of the cab. As for the rail-chariot also the small four-wheeled chariot continued to be used in Greek after the end of Bronze Age being attested also during the Geometric period. |

Some details of the chariot and its fittings emerge from the inventories listed on Linear B tablets at Knossos (dated around 1400 BC) and Pylos (dated around 1200 BC) even if at Pylos the records of chariots are missing, but their existence can be inferred from the inventories of wheels. The chariot frames or bodies are normally indexed separately from the wheels as also attested in the Iliad (*9).

The primary components of the Mycenaean chariot (iqiyo/iqiya) are: amota = wheels; temidweta =

wheel rims; rivets; studs; akosone = axles; spokes; transverse or lateral pole; front-to-rear pole; peqato = foot board; various types of hard wood for tensile strength, such as erika = willow; pterewa = elm; and kidapa = ash wood?; metallic fittings made of kako = bronze (rarely translatable as copper); kuruso = gold & akuro = silver; aniya = reins, usually made of wirino = leather; plus ivory (erepato) and horn (kera) trappings.

|

| Some chariot are fully equipped with yokes, bridles and other necessary fittings; but others are apparently stripped down, and in one case we have an entry which may mean "reduced to constituent members" (me-ta-ke-ku-me-na).The main items listed in addition to the framework are : ivory inlay, bridles or harness, eye-pieces or blinkers (of leather or ivory), a mysterious set of fittings (o-pi-i-ja-pi) made of horn or bronze, a pair of "heels" probably steps at rear for mounting, a "horse follower" which may be a harness saddle of some kind, and also a not well identifiable tube. Some are said to be painted red phoinikiai or vermilion miltowessai. |

|

| Most of the fully equipped vehicles are single or in pairs even if the numbers of plain chariot frames are much larger. The wheels are also listed in considerable numbers. On the large table (Sg 1811) from Knossos a total of at least 246 chariot-frames and 208 pairs of wheels are listed. It would seem likely that as well as a number of luxury vehicles, Knossos could put in the field around 200 chariots.

|

|

In addition to these inventories of chariot, which come mainly from the arsenal building outside the palace proper, we have the remains of a series of small tablets (Sc) from showing fully equipped chariots with the wheels in positon. Few of these tablets are complete indeed they can be interpreted as follows. The first word is apparently always a man's name (whether he is the owner or the driver remains unclear). Then follows a sign for an armour, with the numeral 2, a complete chariot with the numeral 1, and a pair of horses. |

| The word a-ra-ro-mo-te-me-na listed in the tablets (Sd) occurs exclusively with the full chariot ideogram, but minus wheels. It appears therefore to alternate with a-namo-to on the tablets showing the bare chariot-frame, and this is used once with a unique ideogram (Sf 4465), which appears to represent pole and yoke without any cab. |

|

|

Of the tablets found in the arsenal building by Evans in 1904, thirty of the longest deal with chariots. Unlike the single chariots listed on the tablets found in the palace itself (Sc 222), those from the arsenal are shown without wheels, a large number of other tablets from the same building list the wheels separatelly Furthermore the fourteen chariot tablets classified as (Se) were found in the North Entrance Passage of Knossos palace, though showing the same ideogram as the (Sd) tablets, their phraseology is markedly different, even if fragmentary, the references to ivory may suggest more highly decorated state chariots. |

| Appart from tablet (So894) all the two dozen of tablets listing wheel from Knossos were found in the arsenal building. Like mostly of the vase paintings and frescoes, they show a four-spoke design. The majority of the wheels are qualified by one or other of two names of timbers pterewa "elm" and herika "willow" and one or other of two puzzling adjectives describing their construction, te-mi-(ne+ko)-ta and o-da-ku-we-ta. |

|

|

The ZE and MO which precede the numerals are the abbreviatons for "pair" and ",single". When the number of wheels is three pairs or more, the descriptive adjectives are in the plural, as we might expect; even if some inconsistency both at Knossos and at Pylos are present in case of lower numbers. Both "one pair" and "two pairs" generally involve dual adjectives, but "one pair" takes the singular on table (So894) and one a half pairs (three wheels) the plural on table (Sa01). The total number of wheels separatelly listed on the Knossos tablets appears to be over a thousand pairs, but of these the 462half pairs of o-da-ke-we-ta on table (So0446) may perhaps represent a repetitive total. |

The vocabulary and arrangements of the Pylos' tablets listing wheels are very like those of the Knossos series; and their adjectives show similar sequences of neuter duals or plurals according to the number of pairs listed. Pylos has, however, developed a variant of the wheel with surcharged TE, which probably stands for the qualification te-mi-(ne+ko)-ta.

Cypress wood materials, ivory elements, wheels bound with silver or bronze are also listed in the Pylos tablets series (*10). |

|

| The recently tablets in Linear B found in Thebes confirm the presence of war-chariots (i-qi-ja) in the Theban army. Also mentioned are the chariot's beams (a-ko-so-ne) and wooden parts (e-pi-zo-ta). In these tablets are also attested the presence of the horse-keepers, (i-qo-po-qoi) and the cavalrymen or charioteers (e-pi-qoi). |

Despite the general believe the horse mounted warriors were also present during the Late Helladic time, even if our knowledge is limited to some pottery fragments, and very few fresco and sculpture. The horse was fitted with a saddle probably consisting of little more than a padded blanket and the stirrups were as yet unknown. The reins and bridle were probably relatively developed owing to the long tradition of chariotry in Achaean Greece. The role of the cavalry in Achaean warfare is matter for conjecture, since no depictions or descriptions of combat involving cavalry are known. Based of very few depictions the horse mounted warriors seem to be equipped with sword sometimes spear and they worn greaves, helmet and cuirass/corselet or "kiton" . The horse mounted warriors could have fought as cavalry or constituted a force of mounted infantry particularly suited to responding to the kind of raids that seem to have been occurring in the later period, even if their utilization as advanced "scout" can't be excluded.

This pottery fragment from Mouliana Crete dated LH IIIC shows a horse mounted warrior equipped with spear, helmet, a possible small shield and cuirass. |

|

|

Another interesting image of an horse mounted warrior is represented in this sculpture rom Mycenae dated LH IIIB (about 1300 BC). The warriors is equipped with sword beared at chest level and conical helmet. |

| An horse mounted warrior armed with spear is well represented in this sculpture dated about XII century BC displayed at the Kanellopoulos museum of Athens. |

|

|

An horse mounted warrior armed with sword is also represented in this Achaean krater fragment from Minet el Beida Syria dated LH IIIB2 (about 1250 BC). |

| In another fragment coming from the same above mentioned krater a horse mounted man is also depicted, even if in this case no weapons are visible. |

|

|

|

Two horseback riders are also well depicted on a krater from Cyprus dated around 1250 BC . |

| In this krater fragment from Tiryns dated LH IIIB2 a horse mounted man is depicted. Even if no further details are visible this scene was located near a warrior driving a rail chariot. |

|

|

A possible representation of cavalrymen is from this fresco from Mycenae dated LH IIIA/B (about 1350 BC). The warrior behind the horse is clearly equipped with spear, greaves, helmet and what seems to be a quilted "kiton" |

| In a color pottery fragment from Mycenae dated LH IIIC a possible horse mounted warrior behind its horse whose reins he is holding is depicted. The warrior seems equipped with segmentated armour, arm protections, and greaves. A decorated padded blanket is also fully visible on the horse back. |

|

|

A human figure standing upright on the back of the horse is depicted in the large "Grotta krater" from Naxos dated LH IIIC. |

| On a Mycenaean krater fragments from Ugarit Syria dated around 1200 BC some horse mounted warriors are more likely depicted. They seems equipped with a short cuirass probably made of metal scale, neck protection, conical helmet, a belt or "mitra", greaves and a sword. |

|

| A possible evidence of Achaean horseman can be also deduced from the physical remains of a man burried in a tomb at Koukounaries Paros dated LH IIIC. The physical deformation of the bones of an approximately 30 years old man are, according to some scholars (like for instance Sara Bisel), best explained as the result of lifelong horseback riding. |

|

This clay model of a riding woman or goddess from Archanes Crete dated around 1100-1000 BC, Even if not related to a warrior, shows the typic riding method used by the women as well as the large and confortable saddle utilized for this kind of riding. Such figurines have been found in Attica and Crete as well as Anatolia and Near East. |

| A similar rider figurine is also represented in this specimen from Cyprus date around 14th-13th Century BC. Horse riding in Cyprus may have started already during the Middle Bronze Age, as seen on some rare representations on vases, but it received a new impetus during the Late Bronze Age. Riding sidesaddle may have an Aegean origin. |

|

As well explained by Carolyn Nicole Conter in her thesis (*11) the presence of horse bones could be another indication of chariotry in the archaeologiacl record. Unfortunately, this evidences do not occurs frequently in the archaeological record of Greece. The bones that have been found belong to the "Equus caballus" species. These horses were smaller than the average horse today, their height about 1.45m at the withers, corespond to the height of a large pony, indeed they were large enough to pull a chariot.

Of course the presence of horse bones not specifically imply that chariot was practiced, for example when horse bones are normally found in settlement contexts, unless the whole skeleton is found, the bones are normally interpreted as being a food source. The horse burials that have provided evidence for chariotry come from cemetery contexts, but even in these contexts not all horse remains found reflect chariotry. For instance, if only one horse is buried, as in the case of a grave at , then it is not clear if the horse was part of a draught team or if it was ridden. There are

also cases where one or more horses were dismembered at the time of burial, indicating

that the animals were part of the ritual slaughter for the funerary rites. In these cases,

the bones are either piled in or near the tomb, or only parts of the animals may be

recovered from the tomb. Moreover, when whole skeletons are found in pairs it may be inferred that they are chariot teams to serve the dead. |

|

For the Bronze Age only a few sites, Dendra and

Marathon, have yielded the remains of teams of horses. At Dendra two separate pits

were found that contained paired horse burials. The first, dated no later than LH I (about 1550 BC), was

found near the edge of Tumulus B. Both of the horses were placed with their heads facing

northeast and one horse partially overlapped the other. Neither horse had a bit in its

mouth and there was no trace of a vehicle in the pit. The second horse burial

was found in Tumulus C, located northwest of Tumulus B. The horses were again

buried in a special pit located on the northeastern side of the tumulus. Each horse was

lying on its left side. This pair, which is the earliest horse burial found, dates to the. Middle Helladic period. Again, neither horse has a bit in its mouth and there is no trace

of a vehicle in the burial.

Another paired horse burial at Marathon is very similar to the two found at

Dendra. In this case, the horses were buried inside the entrance of the dromos of a

tholos tomb dating to LH IIB (about 1450 BC). Their heads pointed to the entrance of the dromos, and

their bodies lay on their sides facing each other. Again, the horses were placed in a

specially dug shallow pit in which there is no evidence of the vehicle. In addition, neither

of the horses has a bit in its mouth. Therefore, their identification as a chariot draught

team is based solely on their paring and position within the pit. |

The use of the chariot is well documented in the Aegean area since the 16th century BC. This use was more likely diffused in the Greek mainland from the Near East after the Middle Bronze Age (about 1950-1550 BC) as a result of the Central and East Europe migration flows and Achaeans' trade contacts with that region. It seems that the chariot does not seem to have come to the mainland via Crete, but the other way around, in fact It was not until the mid 15th century BC that the chariot appears on the Crete island. The Achaean chariots can be conventionally divided into five main design which can be identify as "box-chariot", "quadrant-chariot", "dual-chariot", "rail-chariot", and "four-wheeled chariot". The "box-chariot" in different variants is present since the early period of the Late Helladic time, this small type of chariot sometimes drive by a single man seems to be utilized until the 14th century BC. "quadrant-chariot" was a rare type of chariot also used since the early period but this model was more likely used also during the transitional and late periods. The most heavy and famous Achaean chariot is the "dual-chariot" it appeared around the middle of the 15th century BC and was utilized (in different variants) since the end of the Late Helladic. Around the 14th century BC appeared a new type of chariot the "rail-chariot". This light vehicle features an open cab and it was more likely mainly used as a battlefield transport than as mobile fighting vehicle. Another rare type of chariot is the "four-wheeled chariot" used since the 16th century BC it has been utilized during all the Late Helladic time. Both the rail-chariot and the four-wheeled one have been continued to be utilized after the end of Bronze Age being also present during the Geometric period.

Even if the question how the Achaeans used chariots in warfare is still controversial, it seems that, based on the pictorial scenes, they did not use their war-chariots in the large squadron mass charges in the manner of the Near Eastern kingdoms and Egypt. There are very few and questionable images of chariots being actually used on the battlefield in the Aegean pictorial art, indeed based on some hunting scene and armed charioteers representations, Linear B tablets as well as Iliad descriptions there is no question that the chariots were largely used in warfare both as platform for throwing javelins (or when possible thrusting long spears), as a means of conveyance to and from battle, and in less occasions as platform for bow-armed warrior. As confirmed by some pictorials, sculptures and human remains the horse mounted warriors were also present during the Late Helladic time. Some elements seem to confirm that the Achaean horseback riding were very able riders, capable of carrying arms and wearing armour while controlling their horses. these warriors could have fought as cavalry or constituted a force of mounted infantry particularly suited to responding to the kind of raids that seem to have been occurring in the later period, even if their utilization as advanced "scout" can't be excluded.

|

(*1) In the Iliad the chariots are not exclusively described as a battlefield transport vehicle but are also used for fighting or limited charge actions: Iliad IV, 306-307 " Any charioteer who reaches an enemy chariot let him stab with his spear from his own car..."; Iliad XI, 150-151 "infantry killing infantry fleeing headlong, hard-pressed, horse-drivers killing horse-drivers..."; Furthermore Homer describes the young Nestor who had once led a successful cattle-raid deep into the territory of Elis, Pylos' northern neighbour. He manages to seize an enemy chariot, whereupon he joints the Pylian chariotry and charges the Epeians, overtaking "fifty chariots, and for each of the chariots two men caught the dirt in their teeth beaten down under my spear" (Iliad XI, 747-748)

|

(*2) Henry Schliemmann TROY AND ITS REMAINS p.36, fig 30.

|

(*2a) Evidence that in the Aegean areas the javelin and the spear were the preferred weapons to be used from the chariot it is also attested in the Iliad when for instance Pandarus, disappointed about the effectiveness of his bow, decided to fight against Diomedes from the chariot using the spear instead of the bow. (Iliad V, 230-238).

On the contrary in the Near East the bow was instead the preferred weapon to be used from the chariot as well represented in several pictorial images.

|

(*3) The Hera's chariot is described with the cab made with a double rails (Iliad V, 728) Even if it is nor clear if this chariot has to be intended as a box-chariot or a rail-chariot type.

|

(*4) Based on M.A. Littauer analysis it seems basically impossible to use thrusting spears between two head-on charging chariots or from an high speeding chariot. M.A LITTAUER & J. H. CROUWEL Chariots in late bronze age Greece Antiquity 221 1983.

Indeed based on Iliad description we can't exclude that in particular situations as for instance a non frontal low speed chariots approach or static actions the long thrusting spear could have been used against other charioteers or foot soldiers.

|

(*5) The Achilles' chariot is described as decorated with bronze (Iliad X, 393). The chariot of the Thracian king Rhesus is described as decorated with gold and silver (Iliad X, 438).

|

(*5a) CHRISTINE MORRIS, Design element analysis of Mycenaean chariot kraters: style, complexity and significance; Pictorial pursuits Figurative painting on Mycenaean and Geometric pottery, edited by EVA RYSTEDT and BERITS WELLS; Stockholm 2006.

|

(*6) Automedont mounts on the chariot and behind him climbs Achilles (Iliad XIX, 395-396)

|

(*7) At least seven references about the chariot box rails or frame are present in the Iliad (Iliad V, 262, 322; X, 475; XI, 535; XVI, 406; XX, 500, XXI, 38)

|

(*8) The wheels of the Heras' chariot have eight spokes (Iliad V, 723)

|

(*8a) B. P. HALLAGER, A warrior and unknown chariot type on a LM IIIB:2 krater in Khania; Aegaeum n.19

|

(*9) The wheels of the Heras' chariot have been installed on the chariot before its utilization on battle (Iliad V, 722)

|

(*10) In the Iliad some of the elements compousing the wheels and relevant fittings of the Heras' chariot are described as made of bronze, silver and gold (Iliad V, 723-726)

|

(*11) CAROLYN NICOLE CONTER Chariot usage in Greek Dark Age warfare. The Florida State University 2003

|

(*12) BLEGEN et al. 1953: 340, fig. 412 no. 6 and 6a.

|

|