|

US Military Aviation

Flight Helmets

US NAVY high altitude |

|

The high altitude helmets and relevant suits have been developed to protect the human body against the lack of pressure and extremes of temperature at high altitude. During the 30s the first experimental presurized suit manufactured by B.F. Goodrich was worn by Wiley Post during an actual flight above 50,000 feet. Early prototypes of pressure suits have been developed and tested during the WWII but the full operative high altitude equipment was introduced in the US armed forces during the late 40s. Because the USAF was already developing partial pressure suits the USN was tasked with developing full pressure suit. After the first prototypes which were lacking in mobility, proper ventilation, comfort and helmet restricted vision. The MK series was succesfully developed in four versions used by US NAVY flight crew from the middle 50s through the early 70s.

Strato Model 7

During 1946, the Navy awarded contract NOa(s)-8192 to the Strato Equipment Company of Minneapolis for the development of a full pressure suit. Akerman designed the Strato Model 7 to provide altitude protection up to 60,000 feet

and limited acceleration protection. The one piece, tight-fitting garment covered the entire

body except the face, which was covered by a detachable “goggle-mask.” The suit, minus

the Government-supplied regulator, weighed 13.25 pounds. The gloves had separate ventilation and pressurization channels to provide comfort even when the suit was not pressurized.

The narrow-neck, close-fitting helmet covered the entire head and ears and was fabricated of

the same material as the suit. Ventilation and pressurization of the helmet was through three

flat, non-collapsible conduits that discharged air just above the ears and into the goggles.

"Donuts" made of soft sponge rubber and chamois cloth protected the ears. The goggle mask

consisted of standard Navy goggles and a pressure-breathing mask integrated into a

single unit. Apparently, the initial Model 7 suit functioned primarily as a full-pressure suit. Akerman fabricated a second Model 7 that could function as a heating and cooling garment, a G-suit, a pressure-breathing ensemble, and a pressure suit, or any combination of the four as needed.

|

|

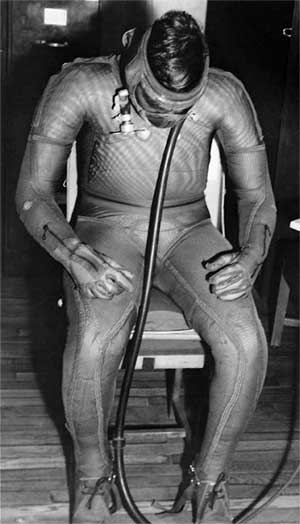

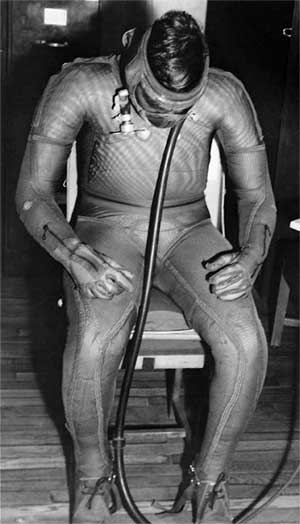

| Many of the early Navy suit dispensed with a hard-shell helmet in favor of a pressurized cloth head covering. Note the large oxygen regulator on the chest. (David Clark Company Inc.) |

|

|

For the Strato Model 7 the "goggle mask" had an internal pressure breathing mask and standard-issued Navy goggles. (David Clark Company Inc.) |

|

David Clark company Experiments and Models

In late 1947, the Navy awarded the David Clark Company contract NOa(s)-9931 for the development of an Omni-Environment Suit for use in emergencies. It appears that, at

least originally, this was a get-me-down suit (and was not meant as a primary life support

system), although one that could be used for extended periods if needed. During the development effort, David Clark Company used alphabetical designators (Experiment A, B,

C, etc.) for in-house experimental suits and numeric designators (Model 1, 2, 3, etc.) for

suits delivered against the contract.

David Clark Company constructed the Experiment A suit primarily to determine how much pressure the selected material would withstand and how much it stretched. The designers used the pattern developed for the Henry partial-pressure suit since it had

essentially the desired size and shape. The suit was sealed at the neck, wrists, and lower

calves, and since nobody would wear it, it did not use a helmet, gloves, or boots.

A second suit, Experiment B, was constructed on November 22, 1948, using a bladder and

case construction technique similar to a G-suit. Neoprene-coated nylon twill bladders

held the pressure, and the basket-weave nylon outer case controlled stretch. David

Clark Company manufactured the bladder to enclose the entire body, except the neck and

head, in a sitting position. An unusual plexiglass helmet was attached using a bayonet seal

at the neck, and a compressed-air fitting was installed in the rear left waist area.

This test provided the confidence for David Clark Company to fabricate the Model 1

that was, in general, similar to Experiment B. The suit approximated the position of a

seated pilot and provided limited adjustment via nylon cord lacings to better fit a variety of

men. Mittens, where the thumb was separate but the four fingers were together, covered the hands. The Navy and David Clark Company both agreed that it would be prudent to test the

absolute strength of the suit by pressurizing it until it burst.

Not wanting to sacrifice the

Model 1 suit, David Clark Company constructed Experiment C for this purpose. David

Clark Company sealed the neck with a circular piece of 0.125-inch-thick plexiglass that

proved to be the weak point in preliminary tests, cracking at 6 psi. The designers replaced

it with a 0.25-inch-thick piece and it was then possible to pressurize the dummy suit

to 10 psi without rupturing it. David Clark Company also created a new helmet with a different neck seal that made it easier to don and doff. The entire helmet

was made of plexiglass with a saddle-piece base contoured to fit the shoulder. Unfortunately,

the helmet could not be used with the Model 1 suit since the shoulder piece made it necessary to lower the rear entry zipper on the suit to a point that it was too difficult to

get the head through the neck opening.

The company fabricated Experiment D in January 1949, building upon what had

been learned. For the Model 1 suit, the pilot donned the inner and outer layers as a single

unit; for Experiment D, the layers were two garments. This meant that a different method

of securing the helmet was needed, and David Clark Company settled on a separating zipper

with one half sewn around the neck of the outer garment and the other half clamped to

the base of the helmet seal. A vertical front zipper that ran from the neck to the crotch

replaced the horizontal back entry zipper.

Experiment E was generally similar to D except that it returned to a horizontal back

entry zipper, and the bladder suit was permanently attached to the helmet. The

five-fingered gloves were also permanently attached to the bladder suit, eliminating

the need for the loops over the thumbs to keep them in place.

Ken Penrod used the stationary F4U cockpit to verify the mobility of the

suit, and he could successfully climb into and out of the cockpit wearing the standard

seat-type parachute and perform all normal piloting tasks. However, rigidity across the

lower waist and groin made it difficult, and at times impossible, for Penrod to bend forward

sufficiently to reach the lower parts of the instrument panel. Researchers noted the crash

harness made it difficult to reach these areas even while wearing only a normal flight suit.

These experiments gave way to the Model 2, fabricated in April 1949. The David Clark

Company made two suits: one to fit a man 6-feet, 2-inches tall and weighing 175 pounds,

and the other to fit a man 5-feet, 9-inches tall and weighing 173 pounds. In general, these

were similar to the Experiment E suit except that all lacing adjustments were eliminated

and each suit was tailored for its wearer.

Based on tests of the Model 2 in Worcester, the NACEL requested that David Clark

Company freeze the design and manufacture a single suit for LCDR Harry V. Weldon.

This Model 3 included a device to resist the tendency for the shoulders and helmet to lift

when the suit was pressurized. One of the major objections the Navy had to the

Model 2 suit was the cylindrical plexiglass helmet, primarily because it was too

large to fit in most fighter cockpits. For the Model 3, David Clark Company made a

helmet using the same fabric as the suit and the inner gas-tight layer was permanently

attached to the inner layer of the suit.

However, under pressure, it was only possible to rock the head back and forth and from side

to side, and even this limited head mobility required a fair amount of extra material

around the neck. To overcome helmet lift resulting from this excess material in the neck,

David Clark Company incorporated a capstan about 9 inches long and 8 inches in circumference

when fully inflated. The capstan was mounted on a curtain fastened to the bottom

of the helmet face frame and to a point on the chest. When the capstan pressurized, inter-digitizing tapes took up several inches of fabric to provide the required counter-pressure. The plexiglass faceplate had sufficient volume to use a normal oxygen mask. David Clark

delivered the Model 3 suit to the Navy on March 8, 1950.

By October 1950, it was obvious to Navy Bureau of Aeronautics (BuAer), David

Clark Company, and the NACEL that the open-weave fabric should be used for the

entire outer garment of a full-pressure suit.

To this end, experimental suits were made to test various aspects of the material.

The

Experiment F suit used a bladder and helmet identical to the Model 3 with an outer layer

of open-weave net fabric. Several different fabrics were used on various parts of the suits

to determine which was best.

The lessons learned from this suit were incorporated into

Experiment G. However, the position the suit assumed when pressurized was not satisfactory—

the legs were too wide spread and the arms were not close enough to the torso.

Further experiments using this suit convinced David Clark that the net fabrics would not

provide a satisfactory answer for controlling torso length although the open-weave fabric limited ballooning and increased comfort for all other areas of the suit.

A different fabric was used for Experiment H, which again used the same bladder and

helmet design as the Model 3. The outer net fabric was finished in such a way as to make it

stiff—an attempt to minimize the "slipping" characteristic (the knots of the fabric moving

along the threads) of net fabrics and to provide greater strength at the seams. The small

gains in these areas were offset by the stiffness, which hindered mobility.

Experiment J returned to the same open weave fabric used on the F and G suits with different

sewing techniques.

For Experiment K, the fabric helmet had a "hole in the top" that eliminated lift and allowed

the head to tilt forward, backward, and to either side. The helmet was built by molding a

plexiglass hat band around the subject’s head, lining the inner circumference with 0.25-inchthick

sponge rubber, and cementing a sheet of rubber over the sponge that extended about

an inch below the bottom of the hatband. A fabric helmet with a plexiglass faceplate was

fastened to the outside of the band.

These experimental suits resulted in the Model 4 suit that was delivered to the Navy

in September 1950. This suit used an outer restraining layer of open-weave nylon net fabric

that allowed significant movement while unpressurized yet assumed the flying position

when pressurized. The snug, lightweight fabric helmet allowed the pilot to wear a standard

flying helmet over it for bump and crash protection. The helmet integrated a goggle-mask

that sealed around the face, isolating this area from the rest of the suit. Unlike the Model 3,

no external accessory straps were needed to combat helmet lift.

Initial tests at the NACEL were promising, and the Navy requested a second suit sized

to fit Harry Weldon. While the suit was being fabricated, David Clark Company

incorporated minor modifications to the respiratory system and added special fittings

at the request of the laboratory, resulting in the Model 4A. In addition to various

unpressurized evaluations, Weldon used the suit in a Link Trainer while inflated to

3 psi. Overall, Weldon thought the suit was workable, but he offered several suggestions

to improve the visibility, arm mobility, finger movement, and ventilation.

The Experiment L suit, which was otherwise similar to the Model 4, had ball-bearing shoulder and wrist joints on one side to allow a comparison with the fabric

joints on the other side. The mechanical joints greatly improved the turning action of the

hand and made it possible to rotate the arm fully.

Based on the apparent success of the ball bearing joints, Experiment M included

bearings at both shoulders and wrists. The wrist bearings were substantially smaller than

the ones used in the earlier suit and allowed a more natural use of the hands.

A deliverable

suit, Model 5, was fabricated to fit Harry Weldon, who tested it in the back seat of a

Lockheed TO2 Shooting Star jet trainer.

Weldon also complained that the mobility of his head was very limited, a known issue

with all pressure suits. Weldon returned the Model 5 to David Clark Company with a

request to improve head mobility. The designers decided to use the same ball-bearing concept

on the neck as they had on the shoulders and wrist.

The Experiment N suit used cloth elbow and knee bellows joints on one side only, along with

the now standard shoulder and wrist rings. In a substantial change, the entire outer layer of

the suit was sewn from the same nylon waffle-weave fabric as the bellows joints. During tests

in Worcester, these joints permitted extremely easy bending while pressurized at 3 psi.

Experiment P concentrated on improving the mobility of the head, and it returned to

a dome helmet instead of the fabric helmet and faceplate. In this case, instead of a rigid

plexiglass dome, David Clark Company constructed a dome made of rubberized fabric

and flexible transparent plastic—essentially, it was a plastic bag placed over the head. A

standard flying helmet could be worn inside the dome, there was no need to individually

fit the domes to each pilot, it was easy to store, and it was not subject to breakage. Although

a seemingly ideal solution, the head bag did not catch on.

David Clark Company delivered three Model 6 suits that were generally similar to

Experiment N, all sized for Harry Weldon, to the NACEL. The inner gas-retaining

bladder was made of neoprene-coated nylon fabric, and the outer layer used nylon waffle-weave fabric. Fabric bellows joints were used at the elbows and knees, and ball bearing

joints were used at the neck, shoulders, and wrists. The shoulder joints used new

stainless-steel radial bearings that were much easier to turn than previous units.

The delivery of the 3 Model 6 suits fulfilled the requirements of the original contract to

deliver 10 prototype pressure suits. David Clark believed that the Model 6 was a workable

pressure suit and could serve as a prototype for production units. The Navy concurred

that David Clark Company had fulfilled its obligations under its initial contract and, on

August 1, 1951, awarded the company a new contract—NOa(s)-51-532c—for continued

work.26 The contract requirements called for an omni-environmental suit that operated

at 3.4 psi and had a leakage rate of less than 5 liters per minute. Almost immediately

after the contract was issued, the need for a full-pressure suit became more urgent, primarily

to support the Douglas D558 research airplane program and the Department of

Defense afforded the development effort an "A" priority.

The Model 7 was a single-piece suit that combined the bladder and restraining

suits into a single garment by cementing 0.020-inch-thick rubber sheet to the inside of

the white nylon waffle-weave fabric used as the outer layer of the Model 6 suit.28 This was one

of the first suits that Joe Ruseckas worked on, "banging metal" for the faceplate. Ruseckas

would later become the head of research and development for David Clark Company.

This suit used the same neck, shoulder, and wrist bearings as the Model 6 suit,

but it had molded, corrugated rubber sections at the knee and elbow joints. The

garment completely enclosed the feet, and insulated boots were worn over the pressure

suit. The Model 7 holds a minor distinction: it was the first full-pressure suit that Albert Scott

Crossfield wore.

Nevertheless, the Navy researchers felt that the suit was unsuitable for operational use,

although it was adequate for use in experimental research airplanes such as the D558.

Almost concurrently with the Model 7, David Clark Company constructed the Model 8,

which used a bladder made of fabric rubberized on only one side along with the restraining

layer made of nylon waffle-weave fabric. The two layers were made from the same

pattern and joined together so they could be donned as a single garment. This suit included

a new type of dome head enclosure consisting of a hard plastic front section with clear soft

plastic portions in the rear quarters and upper forward portion. A standard flying helmet and

oxygen mask were worn inside the dome, with a rubber neck seal to isolate the dome section

from the rest of the suit. The new head enclosure offered almost unlimited visibility but

was extremely large and did not fit inside the cockpits of most contemporary fighters.

The Model 9 and Model 10 suits were essentially similar to the Model 7 using different

fabrics (a waffle-weave Dacron for the Model 9 and rubberized nylon tricot for Model 10).

Both suits were sized to fit Weldon and were delivered to the NACEL in December 1951.

The Model 11 was similar to the Model 8, with a flexible dome head enclosure, but it

had a better overall fit and was easier to don.

The dome head enclosure was similar to the Model 8 and featured a rigid plexiglass front portion. It also used a soft flexible transparent plastic on the forward portion

of the top and the rear quarters for upward and peripheral vision. A rubber neck seal isolated

the dome from the rest of the suit.

The concept of a pressure suit was finally maturing. In November 1951, the NACEL

requested David Clark manufacture two suits, both similar to the Model 7, for use in the

experimental research airplane program at Edwards.

The Model 12 suit was tailored

to fit Crossfield, who needed the suit for continued testing of the D558-II. The

Model 12 used a rubberized Lastex40 inner suit and a nylon waffle-weave outer suit

joined at the same seams so it was, in effect, a one-piece suit.

The Model 12 was taken to Edwards on December 10, 1952, so that Crossfield could

evaluate it in the cockpit of the D558-II. After ingressing and egressing from the airplane several

times, Crossfield decided the suit did not interfere with any normal or emergency functions

he might need to perform. David Clark had brought two different close-fitting helmets,

and Crossfield decided that both designs had worthy features but that neither was satisfactory.

Accordingly, David Clark Company took the best features of both and created a

new helmet that consisted of a facemask with a seal around its periphery that isolated the

wearer from the gas used to pressurize the suit. The mask had two parts—the goggles and

the respiratory mask—separated by a molded rubber partition that helped reduce fogging

of the goggles.

The Model 13, the second of the suits based on the Model 7, was tailored to fit Marine Corps

Lt. Col. Marion E. Carl. A World War II ace, Carl was the last man to set a world’s speed

record under the speed of sound while flying the jet-powered D558-I Skystreak. During

August and September 1953, Carl would make six attempts to set speed and altitude

records using the Model 13 pressure suit in the second D558-II.

The Model 14 was essentially a Model 12 sized to fit Charles C. Lutz of the USAF Aero

Medical Laboratory at Wright Field as part of an exchange of ideas relating to pressure suits.

The Model 15 was a similar suit intended for LCDR Roland A. Bosee at the NACEL, but

the suit was cancelled before it was completed for unexplained reasons.

The Model 16, sized to fit LCDR L. Harry Peck from the NACEL, incorporated some of

the changes recommended by Marion Carl. David Clark Company delivered the suit to

the Navy on January 12, 1953. The suit consisted of a rubberized fabric inner bladder, a

nylon waffle-weave outer restraining garment, and a nylon outer coverall. A pressure-sealing

slide fastener opened circumferentially around the chest, and a waist gusset allowed the

suit to be configured for standing or sitting by opening or closing a nonpressure sealing

zipper on the outside of the suit. Rotatable, nonpressure sealing rings were located at the

neck, shoulders, and wrists.

The Model 16 did not include a ventilation garment, and the evaluators noted

excessive perspiration after extended wear. Despite the apparent failings of the Model

16 to meet operational requirements, the suit provided satisfactory physiological protection

under all conditions, including explosive decompressions up to 53,000 feet.

The Model 17 was a development suit dedicated to fabric shoulder joints instead of the

metal bearings used in earlier suits. Researchers found that these joints were somewhat easier

to fabricate but provided no better mobility.

Model 18 was an entirely new suit sized to fit

John E. Flagg, the director of Research and Development at the David Clark Company.

The suit included structural modifications that made it easier to don, pressure-sealing shoulder

bearings, a redesigned ventilation system, improved glove construction, and a flexible

dome that enclosed a standard-issue flying helmet. The suit was demonstrated at the David

Clark Company facility in Worcester on January 14, 1953, observed by CDR Kenneth

Scott and LT Frank Blake from the NACEL. Joe Ruseckas delivered the Model 18 to the

Navy on April 16, 1953, but the NACEL performed only a cursory evaluation of the

suit since it did not fit any of their personnel. Comments included that the gloves afforded

relatively good feel and mobility and the visor.

Because of this demonstration, the Navy ordered a Model 19 suit sized to fit LT Frank

Blake. The suit was essentially the same as the Model 18 but with a revised facemask and a

helmet sized to fit a McDonnell F2H Banshee, a typical Navy fighter of the era. John Flagg

and Joe Ruseckas took the Model 19 to NATC Patuxent River, MD, on January 18,

1954, for tests in a Douglas F3D Skyknight, selected because of its large cockpit.

|

|

The Experiment B suit in the cockpit of a Vought F4U.

One of the major failing of the Experiment B suit, and most early pressure suit, was a lack of ventilation that caused the wearer to perspire exccessively. (David Clark Company Inc.) |

|

|

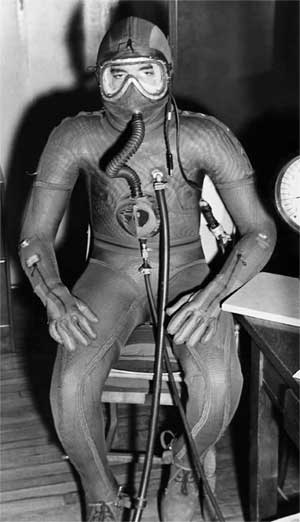

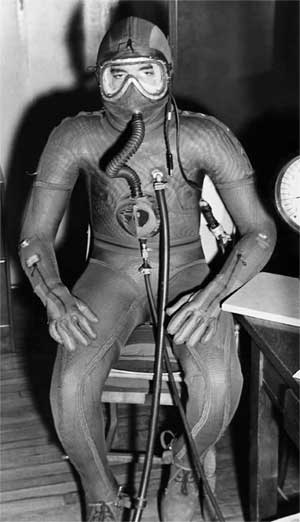

Ruseckart demonstrates the Model 1 during the early 1949.

The Model 1 was generally similat to the Experiment B suit. Note the unusual plexiglass helmet that was attached using a bayonet seal at the neck. (David Clark Company Inc.) |

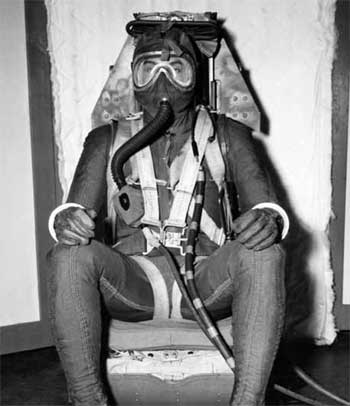

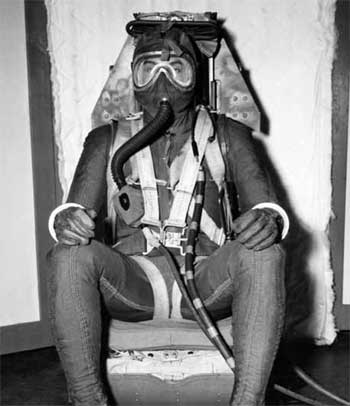

The Experiment D suit used a series of lace adjustments to allow some tailoring to fit various individuals.

The helmet has a built-in earphones. (David Clark Company Inc.) |

|

|

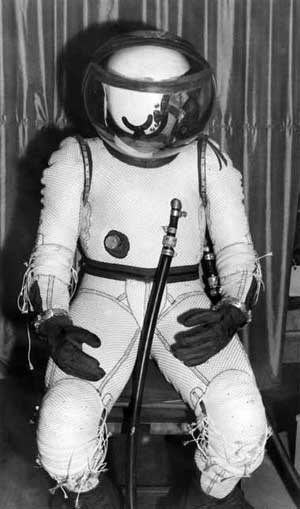

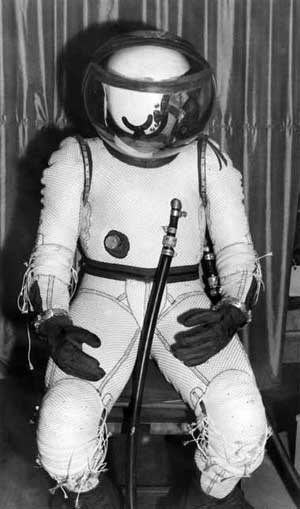

John Flagg wears the Model 2 suit.Note the zippers coming down from the shoulders into the arms, across the upper chest, and vertically down to the crotch. (David Clark Company Inc.) |

The Model 3 was a tight-fitting suit and did not change substantially in appearance as it pressurized.

The unusual clear-plexiglass helmet of the earlier suits gave away to a modified partial pressure suit helmet with a face seal. (David Clark Company Inc.) |

|

|

The Experiment H suit used the same gas container and helmet as the Model 3, but it used a knit-fabric restraint layer that was supposed to control balllooning and increase mobility. (David Clark Company Inc.)

|

| John Flagg shows the "hole in the top"e; helmet used on the Experiment K suit. This innovation largely solved the issued of helmet rise upon pressurization. Unfortunatelly this left the top of the head unprotected. (David Clark Company Inc.) |

|

|

The Model 4A was perhaps the first truly workable David Clark suit. Like many of the previous suit, the Model 4A used a soft helmet. (David Clark Company Inc.)

|

| The Experiment M suit, introduced metal bearing at both shoulders. The wrist bearing were substantially smaller than those introduced on the Experiment L suit. (David Clark Company Inc.) |

|

|

|

The Model 5 suit on january 1951. One of the issues with Navy aircrafts, in particular, is that naval ejection seats used pulling a face curtain down as the means of initiating an ejection. Grabbing these handles required the pilot be able to move his arms up and back-a motion most early pressure suits did not allow while pressurized. (David Clark Company Inc.)

|

| 1951 photo of Model 6 suit demonstration of flexibility while it was pressurized. (David Clark Company Inc.) |

|

|

Although outwarddly resembling the Model 6, the Model 7 suit had the gas bladder and restraint layers sewn together into a single-piece garment. |

| The first suit that David Clark Company delivered under their second Navy contract was the Model 7 for the Douglas D558 program. (David Clark Company Inc.)

|

|

|

|

The Model 7 knit fabric restraint layer was rather delicate, so an outer layer was worn to protect it from snagging on parts of an airplane. A standard crash helmet was worn over the fabric pressure suit helmet to protect the pilot's head. (David Clark Company Inc.)

|

| The Model 8 was mostly a minor evolution of the Model 7, but included a large dome herlmet that greatly improved comfort and allowed a muck better range of head motion. Unfortunately the plexiglass dome was too large to fit into most of fighter cockpits. A standard H-1 helmet was worn under the large dome. (David Clark Company Inc.)

|

|

|

|

The Model 11 was another attempt to find a better solution for the helmet, this time using a flexible dome that was smaller than the Model 8 rigid dome. Also in this suit a standard H-1 flight helmet was worn. (David Clark Company Inc.)

|

| The Model 12 returned to a normal soft helmet, although this one included an integral set of goggles that were hinged at the top and could be opened when the suit was not pressurized. (David Clark Company Inc.) |

|

|

|

The Model 16 used a waist gusset that could be closed to control elongation while the pilot was seated or it could be opened to allow the pilot to stand erect. (David Clark Company Inc.)

|

| The Model 18 was another attempt to provide a large dome that could cover a standard H type flight helmet and oxygen mask. (David Clark Company Inc.) |

|

Cubic Corporation Prototype No.1

Evaluated by the US NAVY in the early 50s the Cubic Corporation Prototype No. 1 high altitude helmet was made in fiberglass painted in bright blue. It had one-half inch of crash padding, foam filler, internal integrated leather helmet with chin rest take up fittings, two buit-in earphones, a mike, a removable visor, quick release oxygen valve unit, rubber neck seal, adjustable cloth retainer colar and quick release ring for neck seal and cloth unit. |

|

| This Cubic Corporation Prototype No. 1 high altitude helmet was sold in a space memorabilia auction in 1998. (Superior galleries) |

|

|

Goodrich Models

For unknown reasons, at the same time the David Clark Company was running out of

funds on its contract, the Navy awarded a development contract to B.F. Goodrich in

Akron, OH. Goodrich was well qualified to develop a pressure suit, having done so

for Wiley Post in 1935 and for the Army during World War II.

After some experimental models the first first truly workable suit to evolve from the Goodrich contract was the Model H of 1952. This suit looked

much like the pressure suits the David Clark Company was developing and, for that matter,

the wartime suits various contractors developed for the Army. It is not clear why this suit was

called the Model H, but interestingly, Colley had developed seven suits for the Army during

World War II, and "H" is the eighth letter. The Model H helmet, gloves, and boots were

permanently attached to the suit torso. The torso construction of the Model H, consisting

of reinforced rubber-impregnated fabric and pleated fabric over rubber pressure convolutes,

was an intermediate step in the evolution from earlier Goodrich suits that had used all

rubber-impregnated fabric construction. The later Model S (which was produced in limited

numbers as the Mark I) eliminated the outer rubber coating, making a lighter and more

flexible (when unpressurized) suit. The Model H helmet used a retractable

visor, a form-fitting headpiece with a crash protection

shell, and a breathing regulator on the facemask. Colley and his assistant project

engineer, Stephen C. Sabo, adopted the same technique used by David Clark for vulcanizing

material to provide elasticity, strength, and stability. Goodrich developed airtight bearings

that could be used at the shoulders and wrists, as well as semi-rigid accordion pleats for the

knees and elbows. Although Goodrich did not intend the Model H to fulfill all the requirements

for an operational suit, initial testing was promising. Researchers at the NACEL

evaluated the suit at 60,000 to 80,000 feet for 11 hours, and its performance indicated it

might be well suited as a mission completion suit instead of just a get-me-down suit.

The Model L was a modification of the Model H that used a detachable headpiece

to make it easier to don.66 The suit weighed 25 pounds, and the pilot needed to use a

separate oxygen mask under the plexiglass helmet. Despite any perceived limitations,

in April 1953, LCDR Harry Peck from the NACEL demonstrated the suit in an altitude

chamber at 70,000 feet.67 By now, the Navy was highlighting that the B.F. Goodrich full pressure suit was, in fact, a "spacesuit" that could operate in a vacuum.

The Model M of 1954 was a significant advance that used the newly developed

Firewel automatic suit controller and eliminated the oxygen mask. Almost all previous

pressure suits had used an oral-nasal oxygen mask inside the helmet to reduce potential

dead air space in the helmet and permit visor defogging The Model M also incorporated

detachable gloves to make donning and doffing easier.

No records could be located

to describe the Model N through Model Q, if such suits existed.

The Model R featured the ability to sit-stand-sit while pressurized and zippers that allowed

the suit to be fitted to individuals. Wire palm restraints kept the gloves from sliding off the

hands when they were pressurized, and the helmet allowed supplementary tinted lenses to

be installed if needed. Tests revealed that the Model R was relatively comfortable and provided

sufficient mobility, but several problems remained before the suit could be produced for

fleet use. The bearings in the joints were sealed against air escaping from the inside but not

against water leaking in—not an ideal trait if one parachutes into the ocean. The boots were

unsatisfactory, and, as with many pressure-suit designs, the helmet continued to lift unacceptably under pressure. The Model R, and all previous Goodrich suits, used an internal

helmet tie down harness that proved unsatisfactory since once the harness was adjusted and

the suit donned, the pilot could not adjust the helmet. In addition, to keep the helmet in

place, the harness had to be tightened to such a degree that it proved uncomfortable to wear

for any prolonged period.

|

|

Goodrich US NAVY Model 3 high pressure suit flight helmet. Developed in the early 50s by B.F. Goodrich, the Model 3 high-presure suit was constructed of heavy rubber and rubberized cloth. Despite its antiquated appearance from the perspective of today, the helmet was literally tied together, this suit included some radical features when introduced. Among them were the close fitting headpiece with oral nasal access passage and the inclusion of a pressure sealing neck bearing.

However, the suit proved bulky and did not provide a great deal of mobility for the pilot. This very early pressure suit suit is now displayed at Naval Aviation Museum of Pensacola. |

|

|

|

|

The first US NAVY high altitude full pressure suit developed by B.F. Goodrich on 1952. Made of rubber, it has a plexiglas helmet that zips open and shut and contain its own oxygen and presure system. The suit has been demonstrated successfully at pressure chamber altitude of 70,000 feet. LCdr. Harry Peck, a naval aviator on the staff of Aero Medical Lab at Naval Air Material Center, was the first man to give the suit a thorough checkout. It weighs under 25 pounds. Under the plexiglas dome the pilot is wearing a modified H-1 flight helmet. (B.F.Goodrich) |

| The torso of the Goodrich Model H used reinforced rubber-impregnated fabric with pleated fabric over the rubber pressure convolutes and was an intermediate step in the evolution from earlier suits that used all rubbers-impregnated fabric construction. A Goodrick high altitude full pressure suit Model H is also display at Naval Aviation Museum of Pensacola. |

|

|

|

|

Model H full pressure suit. Note the helmet pressure regulator that in the first image is unlatched and hanging by the pressure supply hose. The Air Force evaluated the Navy suit in the XB-58 cockpit mockup on April 1954. |

| The Goodrich Model L was generally similar to the earlier Model H but had a detachable helmet. In this case the pilot used a separate oxygen mask inside the helmet. Perhaps the major external change was that most of reinforced rubber-impregnated fabric used on the Model H was replaced by lighter and more flexible fabric. |

|

|

Goodrich Model L full pressure suit (LIFE) |

| A possible early prototype of Goodrich Model H full pressure helmet. |

|

K-1

The high altitude partial pressure helmet K-1, made by international Latex Corporation, was the first mass produced U.S. high altitude helmet in the early 50s. The K-1 was compoused by an internal Hood/neck skirt with rigid frame and by an outer one-piece green fibergalss shell connected to the rigid metal frame of the inner hood. It was used with the T-1 partial pressure suit. The K-1 mainly developed for the U.S. Air Force was also used on limited basis by US Navy with C-4 and C-4A US Navy partial pressure suit which were modified variant of the USAF MC-3 and MC-4 partial pressure suit. |

|

|

David Clark's Joe Ruseckas demonstrates that it was possible to reach the face curtain handles in a North American FJ-3 Fury while wearing and unpressurized T-1 partial pressure suit.

This demonstration convinced the Navy to adopt modified T-1 suit pending the delivery of the dedicated Navy C-1 suit (US Navy) |

| US Navy CDR George Watkins besides an F11F-1F Super Tiger wearing a K-1 helmet and the US Navy C-1 partial pressure suit wich was the modified version of the USAF T-1 partial pressure suit (US NAVY) |

|

|

CDR Watkins with a K-1 partial pressure helmet inner Hood/neck skirt without the outer fiberglass shell. This picture was taken after CDR Watkins' worlds Altitude Record with the F11F-11F Super Tiger. (US Navy) |

K-1 high altitude partial pressure helmet in the color of the US Navy Squadron VF-32 "Swordsmen" as used during the 1958 on F8U-1 Crusader.

This helmet was used with the C-4 and C-4A US Navy partial pressure suit which were modified variant of the USAF MC-3 and MC-4 partial pressure suit. (LIFE)

|

|

|

|

|

Beautiful specimen of US Navy K-1 partial pressure flight helmet. this model has a longer neck skirt like in the MA-2 helmet that was used with additional snaps to connect to the suit helmet (Bellsaviation.com) |

| Another beautiful specimen of US Navy K-1 partial pressure flight helmet with the typical gold paint used in the US Navy flight helmets during the 50s. |

|

|

|

MK-I

Russell Colley and the Goodrich team took the Model R and began to modify it to make

it watertight and improve the helmet tie down system. At the same time, they decided to

incorporate detachable boots to provide more sizing options and improve comfort. Colley

also began to research ozone-resistant materials that would provide a longer life and require

less maintenance for an operational suit. The resulting Model S differed from the

earlier Model R in that it used the diagonal pressure zipper-entry configuration

(as opposed to the U-shaped Model R entry configuration).

The Model S was the

first to employ zippers for glove attachment (Model R had a piston-ring-type latch), and

the suit featured detachable pressure boots and zippered sizing bands in the arms and legs.

Seven rotary-bearing joints aided mobility at the expense of excessive bulk and weight.

The Model S used a helmet tie down system consisting of steel cables that passed from the

headpiece through the crotch in a figure-eight design. Altitude chamber tests showed the

system prevented the helmet from rising under pressure, but the cable tension across the buttocks was uncomfortable to many wearers. As a side benefit, the new nylon restraint materials and streamlined fittings gave the suit a more esthetic appearance Despite not being completely pleased with the new helmet tie down system, in 1954 the Navy in 1954 ordered the Model S into limited production as the Mark I Omni-Environmental Suit.

The Navy conducted operational evaluations in the Vought F8U-1

(F-8A) Crusader, and not surprisingly, pilot feedback centered on the overall bulk and

weight of the suit, the restrictions imposed by the shoulder bearings, and the discomfort of

the helmet tie down cables on the buttocks.

The US NAVY MK-1 or Mark I high altitude full pressure suit developed by B.F. Goodrick in 1956 was thus the very first full pressure suit to actually be used in flight. The helmet incorporated a retractable visor sealed by an inflatable seal and external oxygen regulator. |

|

|

The Goodrich Model S (desiganted by Navy as Mark-I) already exhibited several features that would find their way onto the Navy ultimate Mark IV full-pressure suit. The most obvious was the entry zipper that run diagonally across the chest. Of interest is the figure-eight helmet-tiedown system that ran from the crotch, behind the back, under the armpits and to the helmet. (US Navy) |

MK-I high altitude full pressure helmet. This model do not use the tinted sun protection visor

(Schiffer Publishing Ltd.) |

|

|

The MK-I has the clear visor retractable into a built-in visor housing. (Schiffer Publishing Ltd.) |

| Beautiful specimen of MK-I full pressure flight helmet (Bellsaviation.com) |

|

|

|

Internal suspension system of the MK-I full pressure flight helmet (Bellsaviation.com) |

| Another well preserved MK-I full pressure flight helmet (Steven Wilson) |

|

MK-II

The US NAVY MK-II or Mark II full pressure flight suit was an improvement of the MK-I with improved mobility as well as more comfort than the previous naval high altitude gear. The relevant helmet offered improved visibility and new tiedown system to prevent the helmet from rising under pressure.

|

|

| US NAVY MK-II high altitude full pressure fligh helmet made by B.F. Goodrick in 1957. Also for this helmet the tinted sun propection visor was not used. (Schiffer Publishing Ltd.) |

|

|

|

Beautiful specimen of US Navy MK-II high altitude full pressure helmet of the late of the 50s. |

| US Navy MK-II back side and internal view |

|

|

|

|

Another well preserved specimen of US Navy MK-II MOD 0 high altitude full pressure helmet of the late of the 50s and its internal label.(Steven Wilson) |

MK-III

The MK-III or Mark-III full pressure suit was made by B.F. Goodrick in 1958. The MK-III had an emergency oxygen control system, to be worn as backpack, and a quick disconnect for emergencies. The helmet had both clear and tinted visors mounted on top, rather than under a protective coveras on the MK-I and MK-II. One version of this suit was constructed from a special gold lamè cloth, made especially for the NAVY. |

|

MK-III high altitude full pressure flight helmet. Note the external oxygen regulator with on/off switch. (Schiffer Publishing Ltd.)

|

|

|

MK-III full pressure helmet with tinted sun protection visor in down position. (Schiffer Publishing Ltd.)

|

| MK-III MOD 0 Full pressure helmet used by Naval Air Development Center in 1958. |

|

|

|

Internal view of the MK-III MOD 0 Full pressure helmet. |

MK-IV

The MK-IV or Mark IV full pressure flight suit developed in 1959, was the standard U.S.N. high-altitude suit and remain in service into the early 70s. This suit had better helmet tiedowns, smoother disconnects, and better oxygen regulation, ventilation and control system. The helmet uses an inflattable face seal to seal the clear visor. The Mark IV allowed the pilot to be enclosed in an earth-like atmosphere and in the early 60s was also the basis for the Project Mercury space suit. |

|

MK-IV full pressure helmet made by B.F. Goodrich in 1959. (Schiffer Publishing Ltd.)

|

|

|

MK-IV full pressure helmet with tinted sun protection visor in down position. (Schiffer Publishing Ltd.) |

MK-IV helmet and relevant full pressure suit.

|

|

|

|

Internal part of the MK-IV full pressure helmet. |

| Later variant white painted of US Navy MK-IV full pressure helmet. This variant is marked MK IV MOD 2 Type III of November 1963. From this late variant of MK IV was based the early NASA Space helmets used in the Project Mercury (Heritage Auctions, HA.com) |

|

|

|

|

Very interesting decorated US Navy MK-IV full pressure helmet. |

| US Navy MK-IV with relevat REDAR Hose used on F-4B Phantom II and A-5A Vigilante during the arly of the 60s. |

|

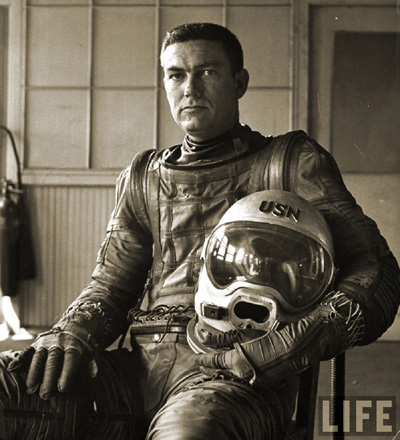

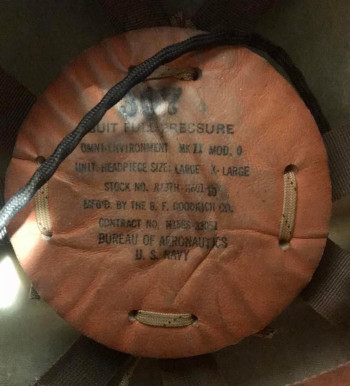

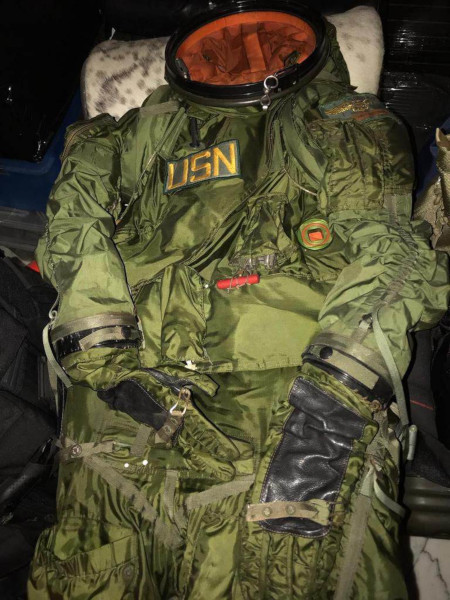

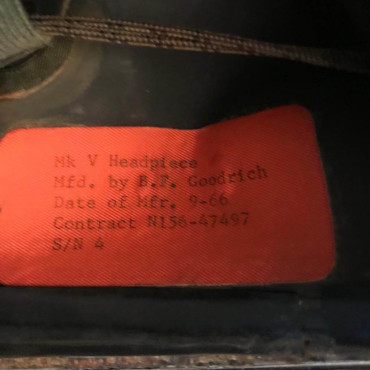

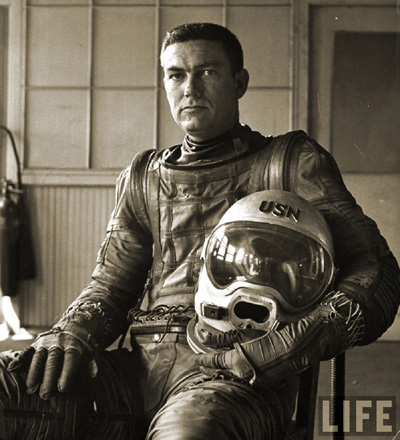

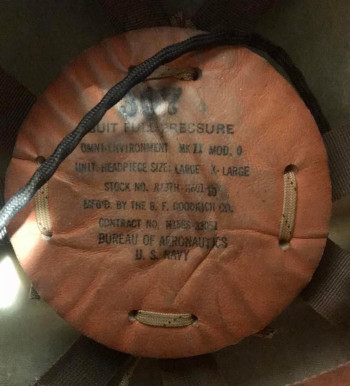

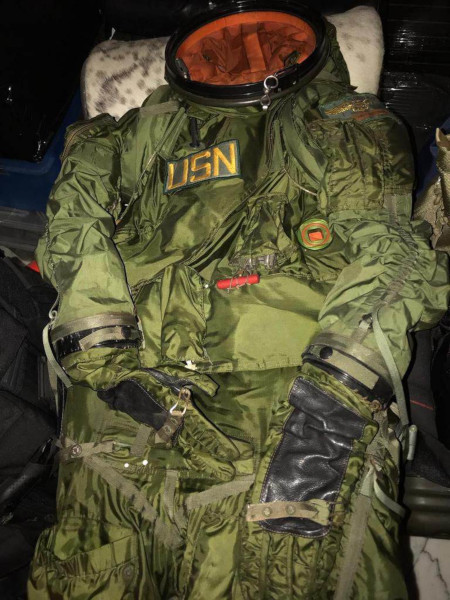

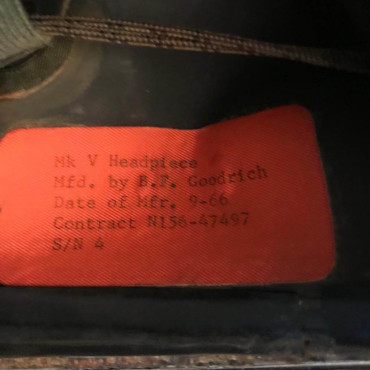

MK-V

The MK-V or Mark V full pressure flight suit developed in 1967 by B.F. Goodrich for the US Navy. It was intended as the replacement of the MK-IV but it never reached the operational status. It is not know if the MK-V was actually tested in flight but it was very likely developed to be use on F-4 Phantom and RA-5 Vigilante. |

|

MK-V full pressure helmet made by B.F. Goodrich in 1967. (Philippe Tondeur collection)

|

|

|

Frontal view of the MK-V full pressure helmet. (Philippe Tondeur collection) |

| MK-V pressure regulator. (Philippe Tondeur collection) |

|

|

|

MK-V and relevat full pressure suit which incorporates the inflattable vest. (Philippe Tondeur collection) |

| MK-V Redar hose in the configration to be used on F-4 Phantom and RA-5 Vigilante. (Philippe Tondeur collection) |

|

|

|

MK-V interlan configuration and relevant label. (Philippe Tondeur collection) |

UNIDENTIFIED HIGH ALTITUDE HELMETS

Some US Navy experimental High altitude full pressure helmet not identified.

|

|

| Possible US Navy experimental high altitude full pressure fligh helmet of unidentified design |

|

|

|

|

Other US Navy experimental high altitude full pressure fligh helmet of unidentified design probably based on MK-IV |

|

|